By Becky Batagol and Genevieve Grant, Monash University

This is a version of the paper we Presented at the National Mediation Conference Canberra, April 2019

This post comes out of a research collaboration between researchers at Monash University and mediation and family services provider, Better Place Australia. We believe this project showcases good practice in industry and academic collaboration.

It arises out of a research project investigating the outcomes and experiences of Family Dispute Resolution (FDR) clients whose last contact with Better Place Australia was 2.5-3 years previously. The project is funded by Better Place Australia, a leading provider of family and relationship services in Victoria who were seeking insight into client experience and outcomes to inform provision of best practice and evidence-based services.

The project is being conducted by our team of researchers from the Faculty of Law at Monash University, Monash Sustainable Development Institute and the Australian Centre for Justice Innovation at Monash.

This post focuses on the difficulty of obtaining long-term data on clients experience after they have left FDR and the importance of collecting such data. We are currently collecting data for this project. The data we have obtained so far is limited.

We contextualise our experiences collecting data from clients who are long finished FDR in terms of the recent Australian Law Reform Commission (ALRC) report, Family Law for the Future — An Inquiry into the Family Law System April 2019. This report, the first-ever whole of system review of family law in Australia’s, proposes an enhanced and better integrated role for FDR service providers and Family Relationship Centres. Such a role, we argue, requires service providers to collect data on the long-terms experiences of their clients.

We ask for readers’ comments at the end of this post about how you have engaged with past clients, especially those long-term clients and what you do with the data collected.

New Roles for FDR Providers in the Family Law System

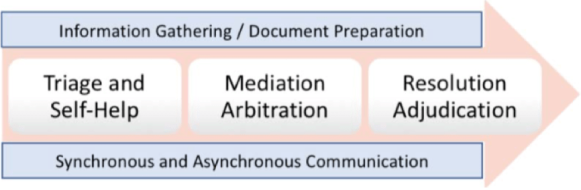

In April 2019 the ALRC’s wholesale review of the family law system was released. For family law support service providers such as those running Family Relationship Centres (FRCs) and providing FDR services, the ALRC found that an increasingly complex client group requires new roles for service providers. In particular, two recommendations are most relevant here:

Recommendation 59: Family Relationship Centres should be expanded to provide case management to clients with complex needs who are engaged with the family law system.

This is an enhanced role for FRCs. The ALRC agreed with the Family Law Council that there are increasing numbers of clients seen at FRCs and in FDR services with complex needs. In 2016 the Family Law Council, in response, recommended introducing case management (recommendation 7) to better support the growing numbers of clients with complex needs seeking assistance from out-of-court family law services.

The ALRC noted that FRC work had gravitated towards FDR service provision. To an extent, this recommendation returns to the original 2006 idea of FRCs as gateways to a range of family law and other services as needed by separating families. It also echoes the Whitlam area idea of the Family Court as a helping court which would assist families experiencing breakdown with both legal and social services.

The ALRC (para 16.34) argued that “introducing case managers to FRCs would ensure that clients with complex needs receive supported referrals to relevant services identified throughout this inquiry that sit outside the family law system.”

Recommendation 60: The Australian Government should work with Family Relationship Centres to develop services, including:

- financial counselling services;

- mediation in property matters;

- legal advice and Legally Assisted Dispute Resolution services; and

- Children’s Contact Services.

This recommendation demands a more integrated role for FRCs and FDR service providers. It recommends that FRCs provide a broader range of co-located or integrated services as a one-stop to better meet the needs of families experiencing relationship breakdown. We note that some FRCs already provide a comprehensive range of services such as financial counselling, legal advice and children’s contact services.

Such case management would also include referrals to and connections with state services such as family violence and child protection services. One option for FRC service provision is that FRCs also tender for state-funded services such as family violence, housing and drug and alcohol services. This would enable service providers to paper over the jurisdictional cracks in the Australian family law system.

Better information on the long-term pathways and needs of FDR clients

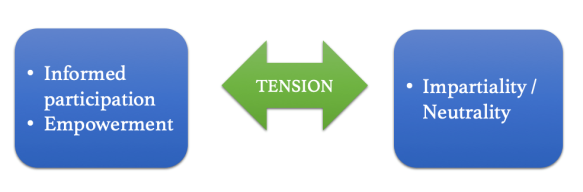

A more integrated and intensive role for FRCs and FDR service providers requires better information on the long-term pathways and needs of FDR clients. Service providers will need to understand and respond to the needs of their clients as they move through the family law system and as family needs change over time. This will require data and engagement with clients over the long term.

While we have some big picture long-term data on family law service system use provided by the Australian Institute of Family Studies, we do not have service and location-specific information for FDR providers on the long-term paths of clients in the family law system.

Long-Term Studies of FDR/ Family Mediation

There is limited longitudinal research into FDR/family mediation, especially in Australia. Work in the US in the early days of divorce mediation showed promising long term outcomes for mediation compared with litigation for child custody disputes.

Pearson and Thoennes (1984) conducted an ‘experimental’ longitudinal study where participants were randomly allocated to a mediation or litigation stream to address their child custody and visitation disputes. The researchers followed up with participants three months after they obtained their final orders and about 6.9 months later (approximately 9 months after final orders). Pearson and Thoennes (1984: 510) found a that the long-term picture for mediation clients depended on whether they had reached agreement in mediation. The researchers argue that the data shows that mediation doesn’t work for everyone and that its benefits are not equally shared (Pearson & Thoennes 1984: 516-7). They state “the benefits claimed for the process seem more accurately to characterise only those who are successful in reaching agreements, rather than all who try.” (510)

Another early US study adopted a very long timeframe in its longitudinal approach to considering the benefits of family mediation (Dillon and Emery, 1996). The study involved a phone survey with participants with disputes over child custody, visitation or child support about nine years after the dispute was first brought to court. 55% of the sample could not be reached by phone (using phone numbers of themselves or family or friends) provided 9 years earlier. 14% of those contacted for follow up said that they did not want to participate in the research because they wanted to forget he painful memories of divorce or lack of time and interest.

Dillon and Emery (1996: 139-40) found that over 9 years, mediation was associated with increased visitation by children with non-custodial parents, better inter-parental communication and more involvement by non-custodial parents in decision-making. However, the 48% attrition rate in this study affects the reliability of their findings. The researchers conclude that more long-term studies of mediation and litigation samples are necessary before conclusions can be reached about the long-term effects of mediation (Dillon & Emery: 1996 : 140).

More recently in Australia, Carson, Fehlberg and Millward (2013) conducted a 3-year qualitative longitudinal study of 60 separated parents who had used FDR. The methodology employed was robust, as it contacted the same separated parents annually for three years after service provision. Remarkably low attrition rate (just 4 left the study in 3 years) because the researchers stayed in contact with respondents annually They found that where both parents were cooperative and able to negotiate, participants who accessed FDR or family law.

Carson, Fehlberg and Millward (2013) found that services where more likely to describe positive experiences and outcomes and satisfaction with the quality of the FDR services they received. However, an uncooperative, controlling and/or violent partner/ex-partner, a hostile post-separation relationship and an absence of the ability to negotiate and compromise, characterised cases where parents were dissatisfied with both the process and post-separation outcomes.

Our Current Experiences Collecting Long Term Data

With Better Place Australia, we have designed a study to investigate the longer-term outcomes of FDR service use following their engagement with Better Place. Our study is a retrospective cohort study with a longitudinal element, meaning that we are studying cohorts of FDR users over time to determine the impact of particular variables on FDR outcomes. We did not follow FDR clients throughout the time since mediation. ‘Longer term’ is defined as 2.5-3 years following last engagement with Better Place. In many cases this may be as long as 4 years since mediation took place. This is a significantly longer period than most long-term studies which tend to focus on mediation clients 12 months after mediation.

Although it is early days for our study, we have had a challengingly low response rate from clients 2.5-3 years since they finished at the service. The service provider emailed out an individually addressed request for participation to the 843 clients who were part of the 6 month cohort we were targeting. We requested completion of a 30 minute survey and invited interested people to sign up for an hour-long telephone interview. A reminder email was sent out. Phone call follow-up for bounced emails. The service provider called every person in the cohort whose email address bounced back (n=40) requesting participation.

Approximately 3 weeks later we had just 25 survey respondents, of which 16 are useful (9 further people commenced but did not provide usable data or are in progress) and six telephone interviews completed. This is a challengingly low response rate ~3% if counting all attempts at completing survey.

We are confident we will achieve a satisfactory response rate for this project. We plan to change the study cohort and involve participants who were more recent clients of Better Place Australia. We may use several other techniques to encourage participation and may supplement the data obtained with targeted focus groups.

How do we Engage with FDR Clients Over the Long Term?

There is an imperative upon FDR service providers to understand client need over the long term in any reformed family law system. This information will need to be specific to the particular client cohort seen by each FDR service provider. National large-scale longitudinal studies are less useful for this task than client and location-specific data.

Our experience collecting long-term data raises real questions about the ability of FDR service providers to engage with former clients over the long term. In our case, we attempted to recruit clients who had not been contacted by the service provider for about 2.5-3 years. Clearly this was too long.

The most successful longitudinal study of FDR, Carson, Fehlberg and Millward (2013), recruited participants while they were still engaged with the service provider and maintained annual contact throughout the three-year study period. Our funding did not permit such a methodology.

A key lesson from our experience is that service providers who wish to understand long-term client experience after FDR should maintain regular contact with former clients in ways that genuinely engages and assist clients. This is a costly exercise. Better Place plan to introduce a 3-6 month follow up survey for all former clients sent out via text message. This will be an additional cost upon the service provider, but the team expect a higher response rate as it will be less like junk email (especially for financial counselling clients).

The recommendations of the Australian Law Reform Commission for FRCs to adopt more integrated and intensive roles within the family law system requires long term data on specific client experiences and need. Accompanying any government contracts for new roles for FRC consortia should come funding specifically for long-term engagement with clients.

For family law clients, their journey through the formal system represents just a small part of the messiness of family breakdown. Funding for engagement with FDR clients over the long-term is a sound investment if we are to truly meet understand and meet the needs of separated families.

Your Thoughts?

We are keen for your thoughts. For those of you who are FDR providers or researchers in the field, how have you engaged with or recruited past clients, especially those long-term clients and what you do with the data you collect?

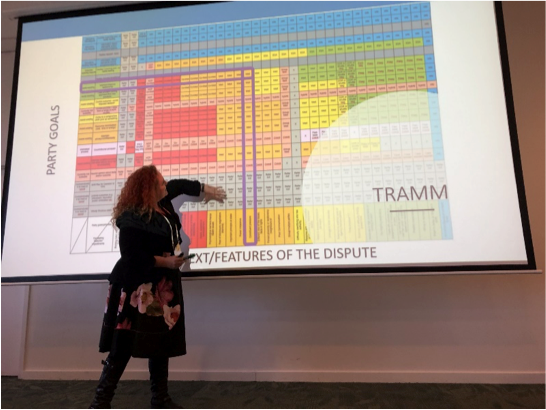

To help get you thinking, here is the final slide of our National Mediation Conference presentation, co-written with the Better Place Australia team, which stimulated a great deal of discussion at our presentation.\

Please comment below! We’d love to hear from you!

We are very grateful to Better Place Australia CEO Serge Sardo and the whole team there who have been such engaged and active partners in establishing, designing and recruiting participants for this research project. We are especially grateful to Graeme Westaway and Jenni Dickson from Better Place who helped prepare this National Mediation Conference presentation.