We have touched on many useful communication approaches in the sequence of recent posts on learning from the art of mediation for the prevention, management and resolution of disputes in lockdown. Nationally accredited mediators are experts in the practice of the mediation process. They are also required to be experts in communication (their own approaches to communication) and in facilitating the communication of others.

This next sequence of posts continues our learning from the theory and practice of mediation – with an emphasis on specific skills for effective communication. We are focussing on five key skills denoted by the acronym LARSQ. LARSQ stands for listening, acknowledging, reframing, summarising and questioning. The LARSQ approach to understanding and enacting effective communication is a common feature of mediation training. If we can train ourselves in lockdown to use LARSQ techniques regularly in our everyday communications, we will be better able to prevent, manage and resolve disputes.

This next sequence of posts continues our learning from the theory and practice of mediation – with an emphasis on specific skills for effective communication. We are focussing on five key skills denoted by the acronym LARSQ. LARSQ stands for listening, acknowledging, reframing, summarising and questioning. The LARSQ approach to understanding and enacting effective communication is a common feature of mediation training. If we can train ourselves in lockdown to use LARSQ techniques regularly in our everyday communications, we will be better able to prevent, manage and resolve disputes.

Effective listening

Effective listening

In a fairy-tale world we would listen to each other carefully and effectively all the time. We would hear factual and content-related messages accurately and we would hear and engage with the messages ‘between the lines’ – those messages relating to emotions, feelings, concerns, interests and underlying needs, hopes and priorities. In such a world we wouldn’t need mediation because mediators would not be required to remind people to listen to each other to achieve proper understanding and acknowledgment.

Lockdown is not a fairy-tale world and we are all waiting to be relieved of its restrictions. In lockdown we are communicating with each other in the context of difficult circumstances – often facing emotional, intellectual and financial challenges. We don’t have a mediator with us everyday to promote effective listening, so we need to harness our dispute resolution agency (see post #2) and all the things we can learn from the art of mediation, to approach our communications with others in lockdown intentionally and in an informed way – so that they are constructive, productive and effective.

A good mediator will spend most of their time listening to the parties. In lockdown communications we need to invest time in carefully listening to each other. Effective listening involves more than simply hearing spoken words. It involves paying attention to, and properly understanding, the various meanings of messages by engaging attentively and being in the moment of communication. This involves: grasping facts and information analytically and picking up on the emotional content, broad narrative patterns and the themes the other person is conveying.

Causes of ineffective listening

Listening may prove to be ineffective due to the following factors relating to the speaker, the listener and the environment of communication:

- Causes of ineffective listening relating to the speaker include — inaudibility, annoying mannerisms, irritating tone, inappropriate pace of delivery, personal presentation, contentious content.

- Causes of ineffective listening relating to the listener include — discomfort, fatigue, focused on responding rather than listening, ignorance of subject-matter, psychological deafness, emotional involvement, inability to absorb, judgmental attitude, device distraction.

- Causes of ineffective listening relating to environmental factors include — external noise, bad lighting, poor acoustics, uncomfortable seating, lack of temperature control, outsider interruptions.

We can contribute to achieving effective listening by avoiding as many of these causes of ineffective listening as possible.

Listening effectively

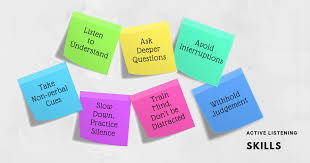

Listening effectively is hard work. It is not a passive exercise. This is why the term ‘active listening’ is commonly used to describe effective listeners. Active listeners are physically attentive, concentrate on and encourage the other speaker, display an attitude of interest and concern, are non-judgmental, are not be preoccupied with responding to or questioning the other speaker, and are not distracted by ‘non-relevant’ matters.

A Master Listener concentrates not only on spoken words and sentences but on the speaker’s patterns of thought, organisation of ideas and the express and implicit themes in their communication. This requires considerable effort. Paying attention is an important principle of listening effectively. Active listening is critical for the activation of the other elements of LARSQ – such as being able to acknowledge emotions and feelings properly, and being able to summarise, reframe and ask questions appropriately.

Elements of active listening

Active listening can be broken down into three key elements – attending skills, following skills and reflecting skills:

- Attending skills include: being present in the moment with the person you are communicating with, both physically and psychologically, making them feel important and engaging their trust by using physical attention, displays of interest, appropriate body movements, and encouraging noises (for example, ‘I see …’, ‘Uhuh …’, ‘Yes …’, ‘Oh really?’).

Gerard Egan (2014, 134) refers to the macro-skills of listening in terms of the acronym SOLER:

- Squarely face the person to show involvement.

- Adopt an Open posture, literally and metaphorically.

- Lean towards the person at times.

- Maintain Eye contact most of the time (if culturally appropriate).

- Relax, be natural in these behaviours.

- Following skills include: indicating that you are following the speaker by providing cues, not interrupting, asking clarifying questions, taking notes, summarising and refraining from being judgemental or giving advice.

- Reflecting skills involve: giving feedback to the speaker about your understanding of their message; identifying and acknowledging facts, feelings and interests; summarising accurately facts, feelings and interests; asking empathic questions. Friends and colleagues of the ADR Research Network – Mieke Brandon and Leigh Robertson (2007, 151–2) – suggest the following verbal cues as ways to initiate reflecting skills:

- ‘You sound/feel as though …’

- ‘You’re saying you believe …’

- ‘What you are saying is …’

- ‘Your point/perspective is …’

- ‘It sounds like …’

- ‘It seems …’

- ‘From where you stand …’

- ‘The main concern for you is …’

Engaging with body language (see posts # 5) is also an important element in active listening. Non-verbal communication can confirm a verbal message, contradict it or scramble it. In our lockdown communications we should aim to identify, clarify and acknowledge the messages in non-verbal behaviours. Much will depend on context.

Detracting from effective listening

We are only human after all and lockdown communications can sometimes be difficult and tense, even with our best efforts. There are many diverse natural impulses which might detract from our achieving effective listening. Here is a sample:

- Focusing on facts and information and ignoring feeling and emotions.

- Asking too many questions, in particular closed, leading or cross-examining questions.

- Moralising.

- Falling into reassurance mode.

- Falling into an advisory mode.

- Judging the other person.

- Lapsing into clichés.

- Slipping into sympathy (as opposed to empathy – see post #16), hooking into the other person’s emotions, values or judgments.

- Engaging in self-exposure.

- Interrupting or finishing other people’s sentences.

Difficult communication situations

The discussion above is premised on the assumption that communications are occurring when people are together – face-to-face. Communication may prove to be even more of a challenge in non-face-to-face environments. For example, on the phone – if we are just using audio – we are entirely dependent on verbal and vocal communication and are unaware of the speaker’s visuals and body language. In these situations we need to make even more of an effort to achieve effective communication.

Some people are just naturally better communicators than others. Some people are inherently and instinctively active and effective listeners. But it doesn’t matter if we aren’t a ‘natural’ at effective listening. We can change that by independently learning to employ the skills and strategies discussed in this post. This is what our dispute resolution agency demands of us in these challenging times of lockdown.

Tomorrow’s Blog: Lockdown Dispute Resolution 101 #16: Effective communication strategies in lockdown – acknowledging.

Acknowledgements

The content of this post was adapted and reproduced from Laurence Boulle and Nadja Alexander, Mediation: Skills and Techniques (LexisNexis, 2020) Chapter 6 (paras 6.40-6.46) with the authors’ permission. Many thanks Laurence and Nadja!

The content of this post was adapted and reproduced from Laurence Boulle and Nadja Alexander, Mediation: Skills and Techniques (LexisNexis, 2020) Chapter 6 (paras 6.40-6.46) with the authors’ permission. Many thanks Laurence and Nadja!

See also: Mieke Brandon and Leigh Robertson, Conflict and Dispute Resolution: A Guide for Practice (Oxford University Press, 2007).

See also: Mieke Brandon and Leigh Robertson, Conflict and Dispute Resolution: A Guide for Practice (Oxford University Press, 2007).

Gerard Egan, The Skilled Helper: A Problem-management and Opportunity-development Approach to Helping (Brooks/Cole Cengage Learning, 2014)

Clouds image: Australian Mediation Association

Listening Emoji: Emoji Request

Active listening image 1: Medium Relationships

Active listening image 2: TechTello

Effective listener image: Alexis Maron

The members of the ADR Research Network have written widely on effective communication in dispute resolution contexts. See for example:

Pauline Collins, Victor Igreja, Patrick Danaher (eds), Nexus Among Place, Conflict and Communication in a Globalising World (Palgrave Macmillan, 2019).

Peter Condliffe, Conflict Management: A Practical Guide (LexisNexis, 6th ed, 2019)

Michael King et al, Non-Adversarial Justice (The Federation Press, 2nd ed, 2014)

David Spencer, Lise Barry and Lola Akin Ojelabi, Dispute Resolution in Australia: Cases, Commentary and Materials (Thomson Reuters, 4th ed, 2018)

Tania Sourdin, Alternative Dispute Resolution (Thomson Reuters, 6th ed, 2020)

Bobette Wolski et al, Skills, Ethics and Values for Legal Practice (Thomson Reuters, 2nd ed, 2009)